Physical examination is an important aspect of diagnosis and it can detect a variety of manifestations, including hepatomegaly, portal hypertension (detected by the presence of hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, varices, and splenomegaly), and chronic liver disease, as well as altered sleep patterns and tremor.2,3,14

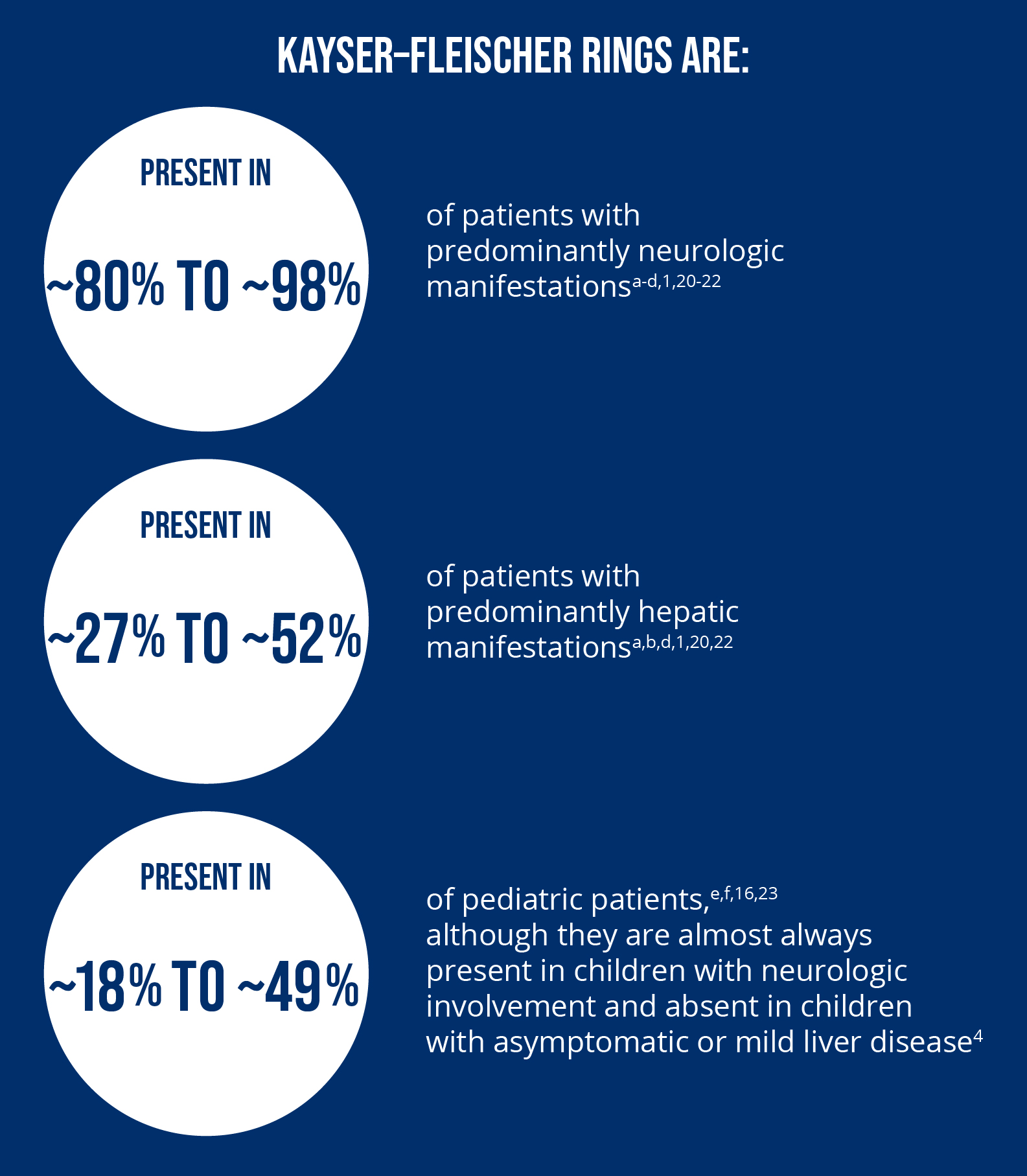

Ophthalmologic examination is another common tool used in the diagnosis of Wilson disease. Kayser–Fleischer rings result from copper deposition in the cornea and can be detected as a golden-brownish ring using slit-lamp eye examination; however Kayser–Fleischer rings are not present in all patients and their absence should not rule out a diagnosis of Wilson disease.3,5,15-17 A slit-lamp examination may sometimes be aided by gonioscopy by an experienced observer.3

Other, new technologies for imaging Kayser–Fleischer rings include:3,18,19

- Anterior segment optical coherence tomography, which can be used for quantitative and qualitative assessment, determining the specific size and location of Kayser–Fleischer rings in the cornea3

- Non-invasive Scheimpflug imaging to evaluate the anterior and posterior parts of the cornea and the anterior chamber angle3,18

- Non-invasive in vivo confocal microscopy to evaluate changes at different regions of the cornea3,19

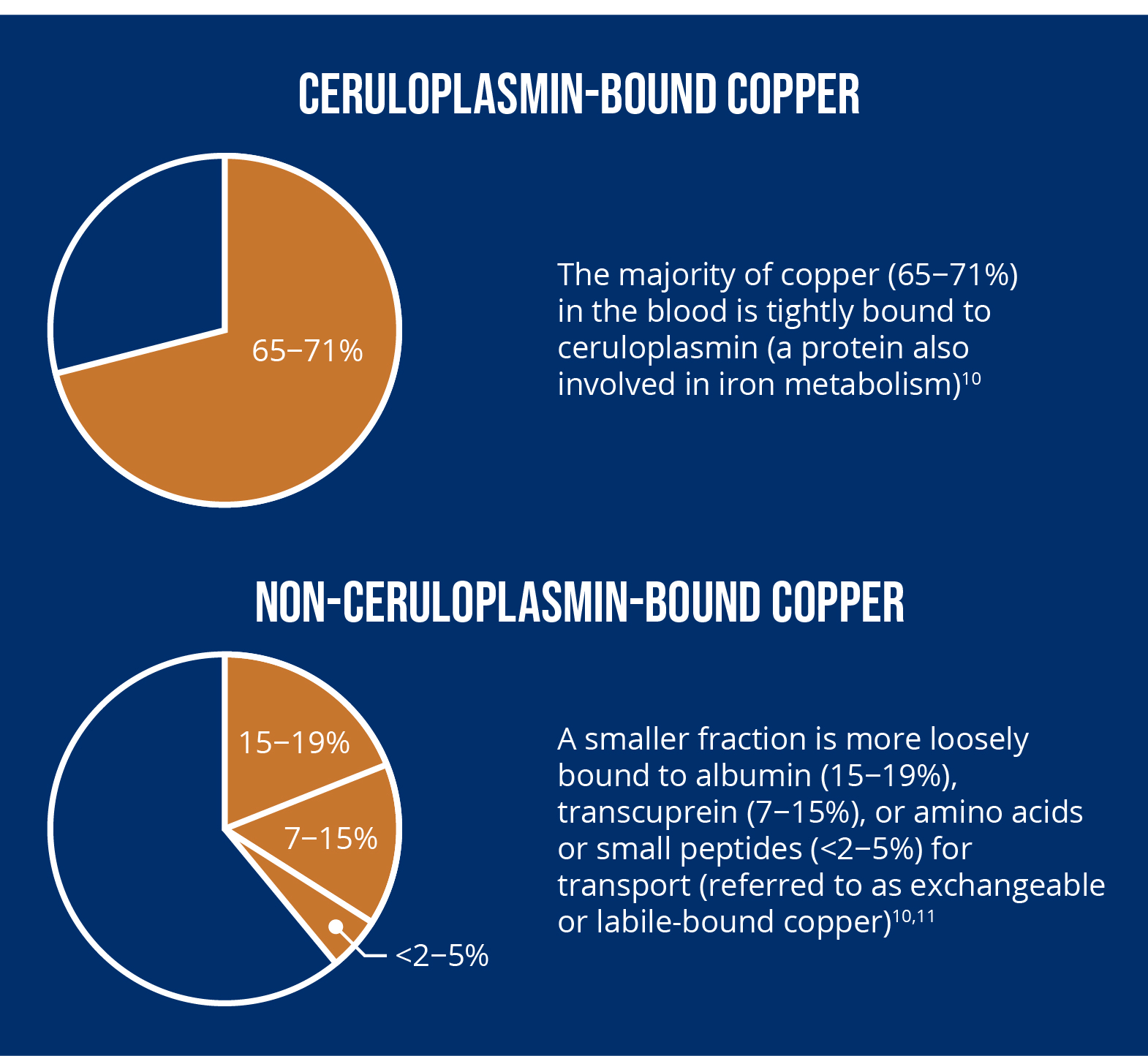

aMethods are being developed to directly measure non-ceruloplasmin-bound copper in order to improve accuracy in research.12,13

Images adapted from information and shown for illustrative purposes only.